Adidas’ attempt to monopolise three-stripes suffers a set back

Adidas registered the three stripe trade mark (shown below) for clothing, footwear and headgear in class 25.

The trade mark was registered as a figurative mark with the description “the mark consists of three parallel equal distant stripes of identical width, applied on the product in any direction”. The trade mark was registered in May 2014. In December 2014, Shoe Branding Europe filed a declaration of invalidity. The Cancellation Division granted the application on the grounds that the trade mark was devoid of distinctive character, both inherently and acquired through use.

Adidas appealed but did not dispute the lack of inherent distinctive character but appealed on the basis that the trade mark had acquired distinctiveness through use. The Board of Appeal dismissed this appeal and Adidas appealed further to the General Court. The points of appeal were:

- The Board of Appeal wrongly dismissed numerous items of evidence on the ground that the evidence related to signs other than the mark at issue.

- The Board of Appeal made an error of assessment holding that it had not established that the mark at issue had acquired distinctive character following use made within the European Union.

Decision

The court talked about the difference in the concept of “genuine use” where trade mark owners are permitted to use a mark in a form differing in elements which do not alter the distinctive character of the trade mark (the starting point here is the registered trade mark is inherently distinctive) and the concept of “acquired distinctiveness through use” where the assumption is that the trade mark lacks distinctive character. The General Court agreed that these concepts are comparable but they applied the test narrowly in this case.

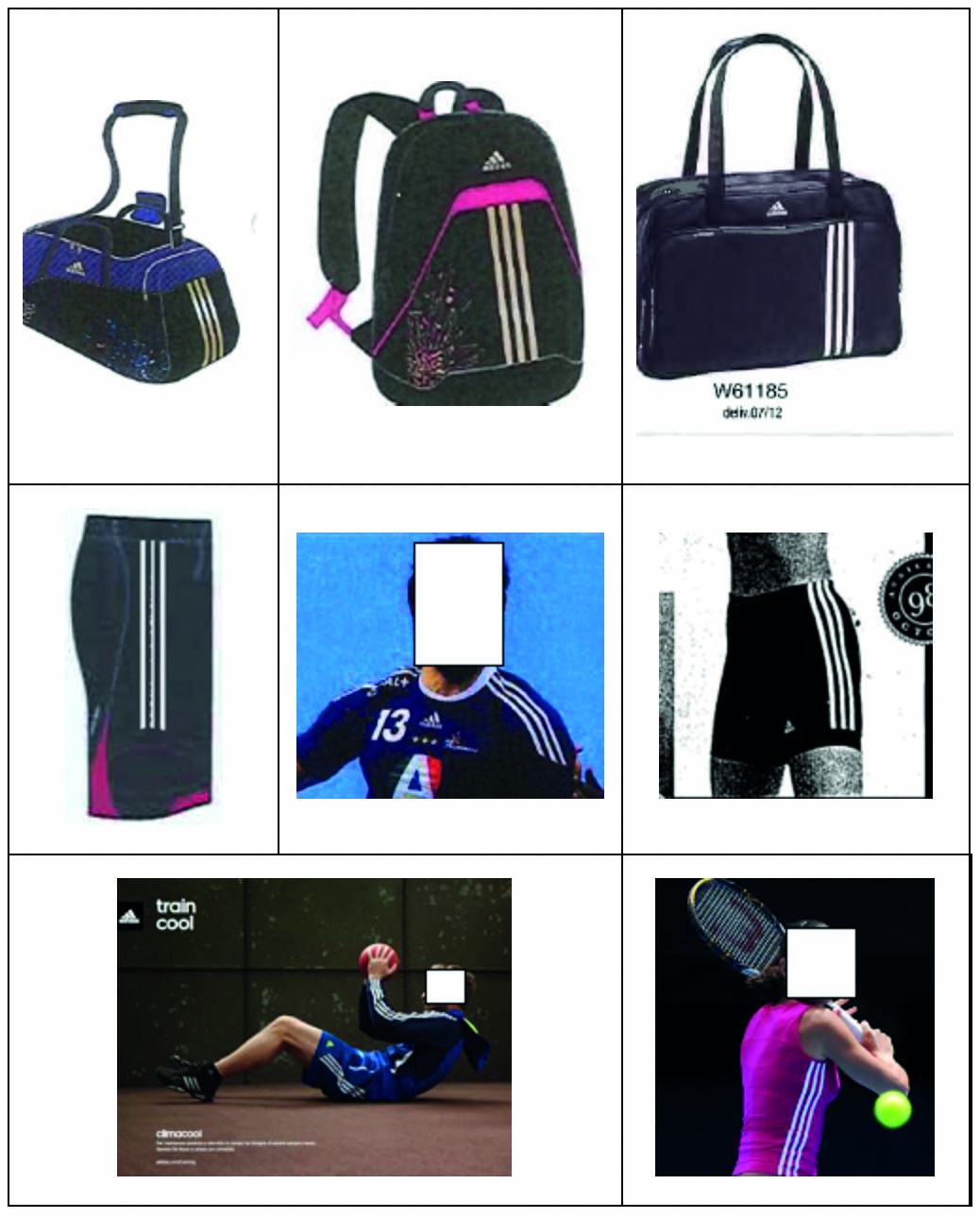

The General Court considered that Adidas’ trade mark was very simple and said that even slight differences in the form could lead to significant alteration of the characteristics of the trade mark. Therefore, the simpler the trade mark, the less likely it is to have distinctive character and the more likely it is that alteration will affect one of the essential characteristics. As part of its analysis, the General Court considered the reversal of the colour scheme. The trade mark is three black stripes. However, a significant portion of the evidence filed seems to be three white stripes on a black background, as shown by the examples below.

The General Court held that the Board of Appeal was right to take account only of the evidence filed in three black stripes on a lighter background.

In terms of the slope and cut some of the evidence showed stripes with different length and width dimensions. The General Court commented that simultaneous alterations to the thickness and length significantly affects the trade mark’s characteristics.

The General Court held that the Board of Appeal was correct to conclude that the vast majority of evidence filed was different than the form registered. Looking at the remaining “relevant” evidence (by the way Adidas filed over 12,000 pages of evidence) the relevant evidence was deemed not sufficient to show a portion of the relevant public would identify the sign.

Adidas’ evidence included:

- Turnover, marketing and advertising figures. These covered all 28 member states.

- An affidavit confirming the vast majority of advertising relates to the trade mark.

- Market share information for Germany, France, Poland and the UK.

- A summary of sponsorship activities including sporting events and competitions.

The figures were described as “impressive” however the General Court held that it was not possible to establish a link between the trade mark and the figures and the goods covered by the registration.

The sponsorship evidence also seemed to relate to the inverted colour scheme. The marketing surveys were conducted between 1983 and 2011 and covered countries including Germany, Estonia, Spain, France, Italy, The Netherlands, Romania, Finland, Sweden and the United Kingdom. As participants of the majority of the surveys had already been asked whether they had encountered the trade mark in relation to sportswear this was considered to influence the results and therefore not relevant.

Other evidence criticised included “reputation” being acknowledged in decisions from various EU national Courts. Adidas had not clearly explained which cases were relevant and why.

Comment

The case demonstrates the importance of filing relevant evidence. It seems that Adidas have fallen foul to the same pitfalls encountered by McDonald’s by filing lots of evidence rather than carefully considering how relevant the evidence is to the trade mark at issue.

Takeaway points

- Think about how your trade mark will be used at the time of application. The simpler the trade mark, the more limited your options for variation will be.

- Take into account the dimensions and colour.

- Evidence of use must clearly relate to the trade mark.

- Most importantly – quality not quantity.

Case details at a glance

Jurisdiction: European Union

Decision level: General Court

Parties: Adidas AG v Shoe Branding Europe BVBA

Date: 19 June 2019

Citation: T-307/17