Heat pumps: peak efficiency?

The UK Government has set out policies and proposals for decarbonising all sectors of the UK economy to meet a net zero target by 2050. The UK Government intends to phase out fossil-fuel boilers, and, as the UK increases electricity production from renewable sources, it is hoped that heat pumps for residential heating will make a major contribution to achieving net zero.

How do heat pumps work?

Air-source heat pumps are generally favoured over ground-source pumps for UK residential properties, since the latter require a lot of space for underground pipework and are typically more expensive.

Air-source heat pumps work by using heat from air outside a home to warm a liquid refrigerant, which then evaporates and becomes a gas. The refrigerant gas is then compressed, raising its temperature and pressure, and is then passed to a heat exchanger, where the heat is transferred into the home’s central heating system. As a result, the refrigerant gas cools and condenses back to a liquid, and passes through an expansion valve, reducing its temperature and pressure, ready to be re-warmed by the outside air: repeating the cycle.

Even when the temperature is sub-zero outside using a refrigerant means that heat energy in the outside environment can still effectively be transferred into the home. By using heat from the surrounding environment rather than a fuel source this allows the heat pump to provide a coefficient of performance (CoP) far exceeding 100%, often as high as 300-400%, meaning that the heat pump is delivering 3-4 times as much heat energy as it consumes in electricity.

Although heat pumps are only recently gaining traction in the UK as an alternative to gas and oil boilers, heat pumps themselves are not new. The heat pump is based on the refrigeration cycle, which was reportedly first demonstrated in 1748, whilst the first heat pump was reportedly built in the 1830s. An early ground source heat pump was patented in 1912, more than 100 years ago.

Room for innovation?

Although the core technology behind a heat pump was reportedly first demonstrated more than 250 years ago, this does not mean there is limited scope for further technical advances. In particular, there continues to be development in pursuit of ever higher CoP, with one highly efficient install in the UK reportedly topping a CoP of 5.5.

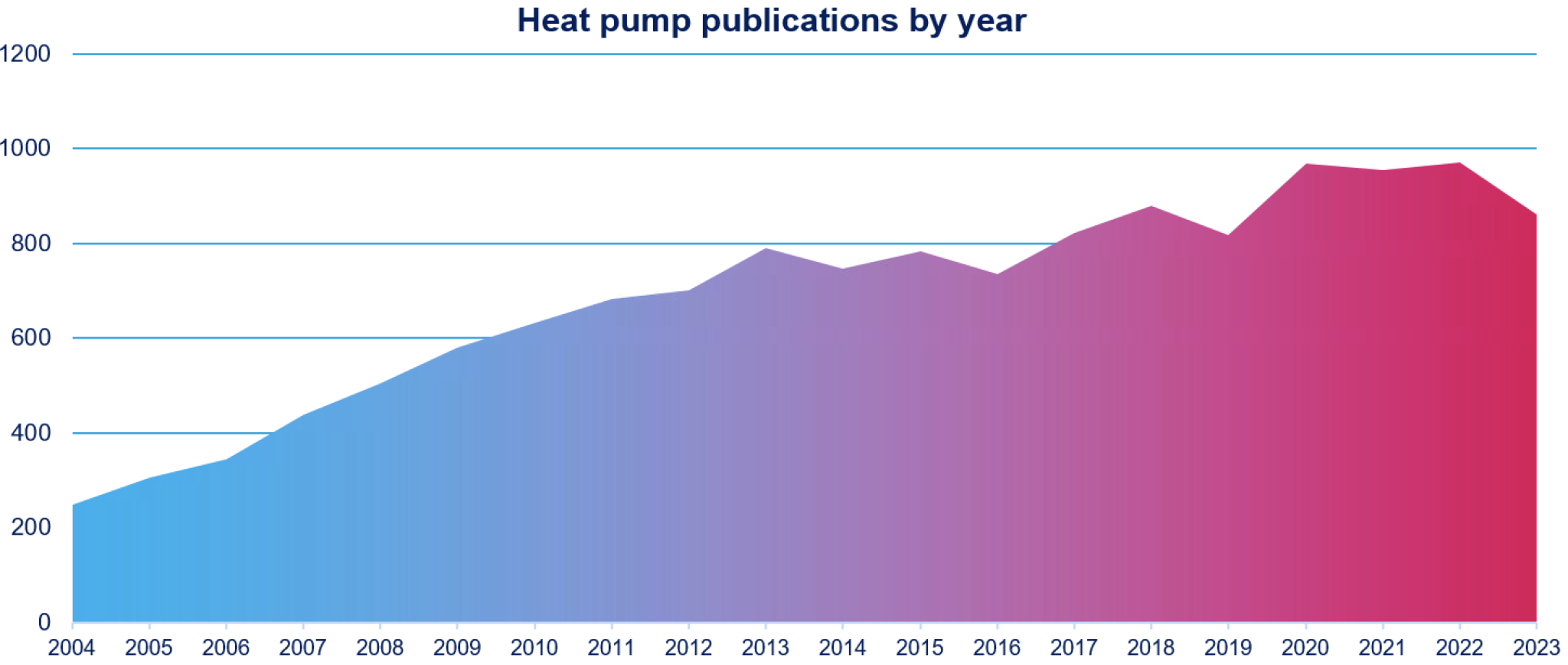

Search terms: “heat pump” in the title or abstract in IPC class F24H: dycip.com/espace-patent-search-heatpump

The number of patent application filings in a given technology area can be a rough indicator of innovation and investment. Interestingly, a search for “heat pump” patent applications reveals a steadily increasing volume of publications from 2004, peaking in 2022 and then stabilising at around 900 publications per year.

Some of the more recent applications are directed to variable speed compressors, which allow a heat pump to consume less energy and operate more quietly. Others are directed improved defrost cycles, which are particularly important since during the coldest winter days, ice can form on the heat pump housing, which may severely decrease the efficiency of the overall system. Meanwhile, further recent applications are directed to adapting heat pump control algorithms based on local current and forecast weather conditions, machine-learning algorithms for predicting hot water demand, and adaptive heat pump control algorithms for modulating energy usage based on time-of-use energy tariffs.

Naturally, these figures do not tell the full story, but it is clear that further investment and innovation is required to achieve a net zero UK by 2050, and it is encouraging to see further developments in this established, but evolving, technical field.

Useful links

- Net Zero Strategy: Build Back Greener, UK Government, 05 April 2022: dycip.com/ukgov-netzeropolicy-oct21

- William Cullen: Time this Scottish inventor was brought in from the cold, The National, 10 April 2022: dycip.com/williamcullen-thenational

- David Banks, Heat Pumps and Thermogeology: A Brief History and International Perspective, 13 June 2022 (paid content): dycip.com/heatpumps-thermogeology-ch5

- The Hunt for the Most Efficient Heat Pump in the World, WIRED, 02 July 2024: dycip.com/most-efficient-heatpump-wired