Icescape v Ice-World patent infringement

To bring about some festive nostalgia in these cold, post-Christmas months, let’s take a look at a judgment related to mobile ice rinks issued by the UK Court of Appeal towards the end of 2018. The case focused on several issues, including priority, groundless threats and infringement. This article focuses on infringement.

The case was between ICESCAPE LIMITED (Icescape) and ICE-WORLD INTERNATIONAL BV & ORS (Ice-World) and was heard on appeal from the UK High Court in which it was decided that there was no infringement by Icescape of Ice-World’s patent EP(UK) 1462755 B1.

This initial judgment was issued before Actavis and thus relied on the use of purposive construction as laid down in Kirin-Amgen.

The judgment on appeal, however, was issued after Actavis. It was thus deemed appropriate by the Court of Appeal to consider the issue of infringement in light of the new law as laid down in Actavis.

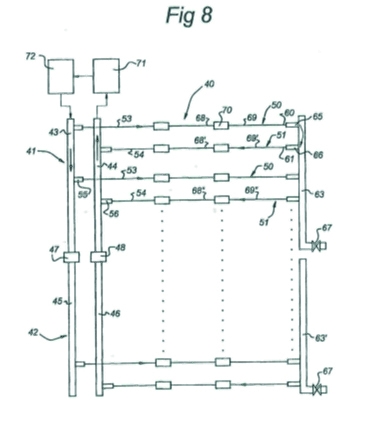

The patent related to a cooling member for a mobile ice rink. Figure A (Figure 8 of the patent) demonstrates the claimed invention.

Figure A represents a set of pipes, manifolds and connectors which sit under an ice rink and through which coolant flows to cool the ice rink. More specifically, coolant previously cooled by a refrigeration unit is pumped to a feed manifold (43, 45) from which it then flows through multiple longitudinal pipes (50). Once it reaches a connecting pipe (63), the coolant is returned via further multiple longitudinal pipes 51 to a discharge manifold (44, 46). The coolant is then pumped from the discharge manifold (44, 46) back to the refrigeration unit and the cycle is repeated.

For mobile ice rinks, the various elements are connectable and disconnectable from each other so as to allow the ice rink to be assembled and disassembled. The assembly and disassembly remains, however, a time consuming and laborious process.

In order to alleviate this problem, the longitudinal pipes (50, 51) of the claimed invention are made up of a plurality of rigid pipe sections (68, 68’, 68’’, 69, 69’, 69’’) connected to each other via joint members (70) which enable adjacent rigid pipe sections to fold back on one another. The rigid pipe sections forming each longitudinal pipe (50, 51) therefore do not need to be connected and disconnected from each other during assembly and disassembly. Rather, they can just be folded and unfolded, thereby saving time and labour. It was determined that this was the inventive concept of the claimed invention.

Some connection and disconnection was still necessary, however. In particular, the claimed invention has multiple elements (41, 42) each comprising a feed manifold (43, 45), discharge manifold (44, 46) and longitudinal pipes (50, 51). It can be seen that element (41) has feed manifold (43) and discharge manifold (44) and that element (42) has feed manifold (45) and discharge manifold (46). The manifolds of adjacent elements are connected together via coupling members (47, 48) to form an enclosed network of pipes around which the coolant flows. It was the nature of this connection between the manifolds of adjacent elements upon which the issue of infringement rested.

In particular, it was accepted by Icescape that its rink had all of Ice-World’s claimed features except:

- D. wherein the first and the second element (41, 42) can be placed in the operational position alongside one another such that the feed and discharge manifolds (43, 44, 45, 46) of the elements extend in the extension of one another in the transverse direction, and

- E. wherein the feed and discharge manifolds of the two elements are provided with a coupling member (47, 48) to make a fluid-tight connection between the respective feed and discharge manifolds of the first and the second element.

(The features are denoted “D” and “E” to reflect the notation used in the judgment).

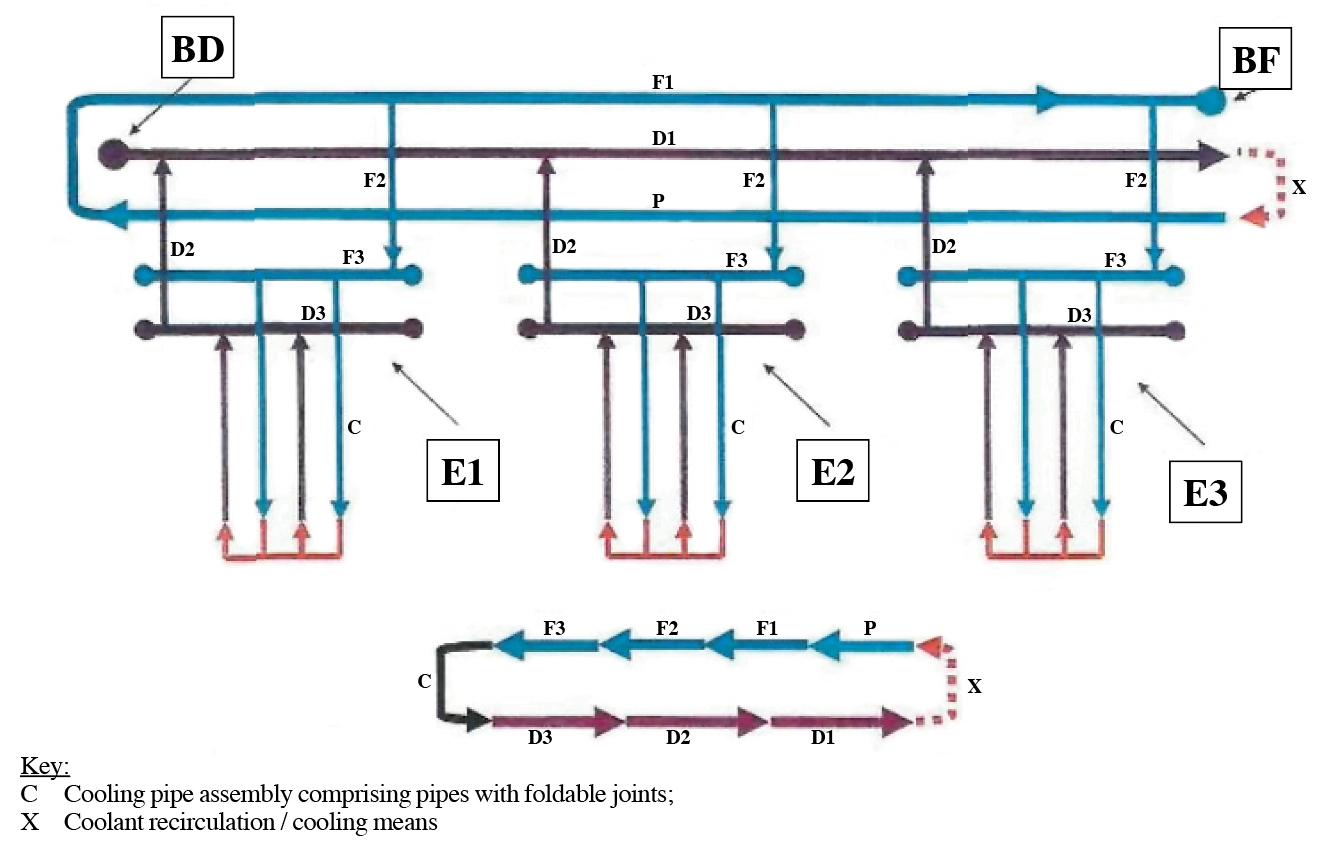

Figure B shows a schematic of Icescape’s rink.

Icescape’s rink operated under the same basic principles as the claimed invention. In particular, refrigerated coolant flows from a manifold F1 to further manifolds F3 of each of a plurality of elements E1, E2 and E3 via connecting pipes F2. Each element E1, E2 and E3 has longitudinal pipes C which, like the longitudinal pipes (50, 51) of Ice-World, have foldable joints. Coolant flows along the longitudinal pipes of each element E1, E2 and E3 (thereby cooling the rink) and is returned to further manifolds D3 of the elements E1, E2 and E3. The coolant is then returned to a manifold D1 via connecting pipes D2.

The High Court decided that there was no infringement because Icescape’s rink did not have feature E when construed purposively under the principles of Kirin-Amgen. In particular, it was determined that the infringement claim ignored the language of the claim and involved replacing feature E with either nothing at all or with language such as “wherein the feed and discharge manifolds of the two elements are connected into the system in some leak-free manner”.

The Court of Appeal agreed. It was determined that integers D and E had to be read together and that, under a “natural reading” of these integers, the skilled person would have come to the conclusion that the two manifolds of each element must be connected together in series (rather than in parallel, as in Ice-World’s case, due to the use of the further manifolds F3 and D3) so that fluid does not leak between them from one to the other.

This was not the end of the story, however. It was determined that, after the claims have been construed purposively, the questions laid down in Actavis regarding immaterial variants also needed to be considered.

It was found that Icescape’s rink did differ from the claimed invention in ways which were immaterial when the Actavis questions were applied, and that Icescape therefore did infringe the patent.

In coming to this conclusion, the judgment appears to put a lot of weight on the distinguishing features of Icescape’s rink in the context of Ice-World’s inventive concept. Specifically, it was determined that the inventive concept was the use of the joint members of the longitudinal pipes which allowed the rigid pipe sections of the longitudinal pipes to be folded on top of each other, thereby allowing rapid and reliable installation of ice rinks with a large number of different possible surface areas. Icescape’s rink had this feature and the differences in the ways in which adjacent elements were connected together (ie, a “parallel” rather than “series” arrangement) had “nothing to do with the inventive core of the patent”.

This case thus nicely demonstrates the new approach to infringement analysis following Actavis in which two issues (referred to as issues (i) and (ii) in the judgment, referring to Actavis) must be considered. Issue (i) is essentially purposive construction (as before). Issue (ii) is whether the alleged infringement differs from the claimed invention in immaterial ways, based on the Actavis questions and the inventive concept of the claimed invention. In effect, issue (ii) gives the patentee a second chance at proving infringement which was not available under Kirin-Amgen, a chance which bore fruit for the patentee in this case (although the patent was ultimately found to be invalid).