IP litigation - what not to do! Avoidable errors in recent UK High Court design cases

Four recent UK High Court judgments contain timely reminders of the various legal and procedural issues that may arise in the context of intellectual property litigation. Focusing on design rights, this article discusses a high profile damages inquiry, the perils of owning a commonplace registration, the difficulties with searching for obscure prior art post-infringement, and how providing evidence by video-link at trial can go horribly wrong.

Related webinar

Agnieszka Stephenson presents a short webinar summary of the four cases covered in this article. This is now available on demand.

Read moreIs a “London England” hoody registration enforceable?

Ahmet Erol v Posh Fashion looks at a claim for registered design infringement before the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (IPEC) and a counterclaim for invalidity, and demonstrates that the mere existence of a design registration does not necessarily provide the owner with an enforceable right.

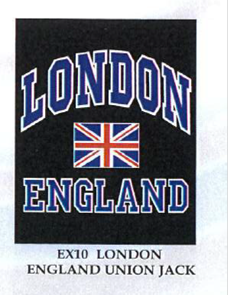

The registered designs essentially amounted to the “London+Flag+England” legend as seen below.

Although there was some discussion about the extent of the design it was held, and not contested, that, due to their ubiquity, the hoody, T-shirt and colours used did not have a material impact on the extent of the design rights or the outcome of the case.

The main issues were whether the designs were new and had individual character in May 2011, and whether the defendant’s garments produced a different overall impression from the registered designs on the informed user.

Insofar as validity of the two designs was concerned, the defendant relied on three alleged items of prior art, including the image below, allegedly from 1999:

Oral evidence was also given contending that the “London+Flag+England” legend designs were used widely before 2011.

A design has individual character if the overall impression it produces on the informed user differs from the overall impression produced on such a user by any design which has been made available to the public before the relevant date.

Even assuming the first design was novel notwithstanding the prior art shown above, the judge contended it must lack individual character since the overall impression in both cases was the same.

For the second design, there was a strong case for anticipation (lack of novelty) because the evidence specifically mentioned the colour “grey” in relation to T-shirts.

Both designs were held to be invalid and the infringement claim automatically fell away.

The search for obscure Spanish riding boots

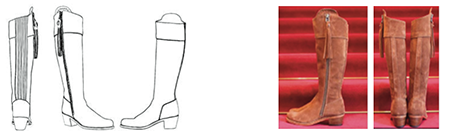

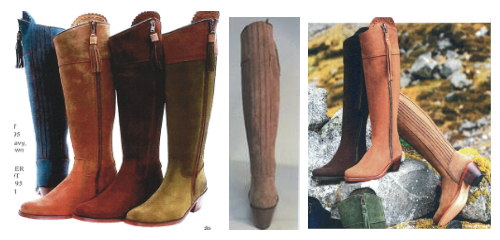

In Fairfax & Favor v House of Bruar, the claimants alleged that the defendants infringed their UK unregistered design rights (UKUDR) and registered Community design (RCD) rights in the Heeled Regina (shown below left) and partial designs (shown below right) through sales of the defendants’ Version 1, 2 and 3 boots.

The claim was issued before Brexit and the claimants relied on their RCD. No application was made to amend the claim to assert reliance on the cloned UK equivalent design but it was considered unnecessary to distinguish between the two. The judgment, and this article, therefore refers to the registered design as the RCD.

The defendants unsuccessfully challenged the validity of the RCD and argued the partial designs and the Heeled Regina were not protected by UKUDR because they were commonplace. Notably, however, the most similar prior art design (shown below) was only detected in the course of litigation through extensive searches of solicitors and could not be relied on, as there was nothing to indicate an awareness of that boot by the defendants or designers in the field when the Heeled Regina was created. Miss Recorder Amanda Michaels found that the prior art was obscure and would therefore not render the design commonplace, and cautioned against conducting overly-extensive searches for appropriate designs after infringement has already occurred, purely for the sake of justifying that infringement.

In any event, the Heeled Regina’s elasticated panel with leather strips was a particularly original feature. The Heeled Regina was thus protected by UKUDR, and the RCD was valid for essentially the same reasons.

With the UKUDR and RCD’s validity intact, the Version 1 and Version 2 boots were found to be infringing, as they had been copied and substantially made to the Heeled Regina. However, the Version 3 boot was not infringing due to the different placement of the elasticated panel - a significant step away in design terms. The Version 1, 2 and 3 boots are shown below.

The partial designs, however, were commonplace, and those infringement claims failed.

Following the trends a little too closely

In Original Beauty v G4K Fashion, Mr David Stone dealt with a High Court damages inquiry following findings in previous trials that the defendants (trading as Oh Polly) infringed House of CB’s UKUDR and Community UDR in respect of seven garments.

It had become obvious that the defendants sent images of the claimants’ designs directly to their factory to be made up, and had been dishonest in oral testimony and material documents - which they had not drawn to the court’s attention.

The claimants sought damages under three heads:

1. Lost profits on garments which, but for the defendants’ sales, would have been made by the claimants

The lost profits were calculated by multiplying the lost sales of the infringing garments by the per-unit profit for the claimants’ garments incorporating the respective infringed designs. In the lost sales analysis, Mr Stone assessed that 20% of the 15,393 sales of the infringing garments had been made to customers who probably would have purchased the respective claimants’ garments had the infringing garments not been available. Mr Stone was mindful of the Ultraframe, Gerber, General Tire and Watson guidelines to be liberal in the assessment of that probability, and the need to form a general view in his judicial estimation, noting that such estimations cannot be wholly scientific.

2. A reasonable royalty on the defendants’ sales not covered by the lost profits

In considering the hypothetical royalty a willing licensor and licensee would have agreed, had the infringement not occurred, Mr Stone found the parties would have agreed to calculate an above-average royalty rate (10%) based on the defendants’ net sales revenue, given the defendants had no other source of on-trend designs from a successful business. The claimants also would have wanted a minimum licence fee to ensure that the licensing income was worth the administrative effort. The royalty would have diminished the defendants profits but not render the garments ‘loss-leaders’.

3. Additional damages, given that the infringement was flagrant

Additional damages in the UK are not a fine but may be punitive and have a valuable deterrent effect. Mr Stone considered the serious and flagrant nature of the defendants’ four-year infringement, and their denials of copying throughout the trial. He considered an award of £300,000 (a 200% uplift on the standard damages) would be sufficient to “punish” the defendants and deter them from infringing again.

The total damages amounted to just over £450,000, one of the largest sums awarded in the context of unregistered design infringement.

A salutary tale in a post-Covid world: evidence by video-link went very wrong

In our fourth and final case, ASR Interiors Limited v AWS Trading Limited, an action for UK registered design infringement is less notable for its legal substance than for its teachings on the perils of witness testimony.

The case concerned the infringement of three UK registered designs shown below left by the furniture items shown below right.

The defendants counterclaimed for invalidity on the basis that each of the infringing products pre-dated the registrations. Thus, much of the evidence concerned whether there had been prior disclosure of the ‘accused’ designs. Unfortunately for the defendants, things did not go well:

- The first witness did not attend for cross-examination;

- The second witness was found to be “belligerent”; and

- What transpired when the third witness, Mr Singh, gave evidence via video-link, cannot be recounted any more vividly than in the decision itself:

“The first time contact was made with Mr Singh, he appeared to be driving a van, dividing his attention between the road and a camera on the passenger seat. I immediately stopped the hearing.

The second time contact was made [once Mr Singh had stopped driving], Mr Singh appeared to be in a busy office with distracting background noise. I asked him if he could find a quieter place. This appeared to be a store room in the office.

After being sworn it turned out that he had left his witness statement in the busy office. He left the video link running while he went back, then returned to the store room with it.

He was asked about his exhibit to his witness statement, but he did not have that exhibit with him [or] know where it was. Similarly he did not seem to know about a brochure to which he had referred.

At this point [the 1st Defendant’s counsel] wisely accepted that the process was not turning out to be a successful one, and indicated that he would simply rely on Mr Singh’s statement for such weight as it might be thought to be worth. This was again realistic. In those circumstances I give Mr Singh’s statement no weight.”

The judge made no determination as to who was at fault in relation to the above events. The salutary lesson, however, particularly as regards video-link evidence, is to appreciate the potential consequences when things go wrong.

Anyone who obtains an order permitting video-link evidence would be well advised to think carefully about how the process of giving evidence will actually happen. At a bare minimum, when the time comes for the video link to be activated the witness should be in a quiet room with all the case papers. Otherwise the risk is that the evidence will not be given properly, with potentially adverse consequences for that party’s case.

Unsurprisingly, the registered designs survived the invalidity attack and were held to be infringed.

In short

The above cases demonstrate that, without prior preparation, IP litigation might not go ahead exactly as planned.

It is worth considering the state of the market and conducting clearance searches prior to launching a new product or registering a new design or trade mark. And if litigation has commenced despite taking these steps, it is crucial to ensure that witnesses are prepared for the practicalities of adducing evidence, and do so in an honest manner.

Taking any of the above measures might have resulted in significantly different outcomes for the affected brand owners.

Case details at a glance

Jurisdiction: United Kingdom

Decision level: High Court

Parties: Ahmet Erol v Posh Fashion Ltd

Date: 08 February 2022

Citation: [2022] EWHC 195 (IPEC)

Link to decision: dycip.com/erol-posh

Jurisdiction: United Kingdom

Decision level: High Court

Parties: Fairfax & Favor Limited & others v The House of Bruar Limited & others

Date: 25 March 2022

Citation: [2022] EWHC 689 (IPEC)

Link to decision: dycip.com/fairfax-bruar

Jurisdiction: United Kingdom

Decision level: High Court

Parties: Original Beauty Technology Company Ltd & others v G4K Fashion Ltd

Date: 20 December 2021

Citation: [2021] EWHC 3439 (Ch)

Link to decision: dycip.com/original-beauty-g4k

Jurisdiction: United Kingdom

Decision level: High Court

Parties: ASR Interiors Limited v AWS Trading Limtied and Giatalia International Limited

Date: 24 February 2022

Citation: [2022] EWHC 372 (IPEC)

Link to decision: dycip.com/asr-aws-giatalia