Life after G 2/21: plus ça change, plus c’est la méme chose?

This article was first published in the March 2024 edition of the CIPA Journal, based upon a presentation given at the CIPA Life Sciences conference in November 2023 and co-authored with Amanda Simons. This article has been updated to take account of more recent European Patent Office (EPO) decisions relating to the reliance of post-filed evidence to demonstrate an inventive step.

Time flies. It seems hard to believe that a year has now passed since the Enlarged Board of Appeal issued its much-anticipated decision in case G 2/21. It is fair to say that the initial reaction to the decision amongst the IP fraternity was mixed, at best. Now that the jurisprudential dust has settled somewhat, the practical ramifications of the decision are becoming clearer to see.

This article summarises the Enlarged Board of Appeal’s decision in case G 2/21 and considers some of the emerging themes which arise from it, with reference to more recently published decisions of the EPO Boards of Appeal.

Life before G 2/21

Some might say that, in an ideal world, there would be no need for the reliance upon post-filed evidence to demonstrate inventiveness (or anything, for that matter). Surely, patent applications need simply be drafted so as to include all of the relevant technical information that is necessary to adequately “showcase” the invention for which protection is sought. And so, as the saying goes, pigs might fly.

Graciously, the EPO has for many years appreciated that it is not an ideal world and, in doing so, permitted the reliance upon supplementary (post-filed) information to rebut objections relating to a lack of inventive step in both pre- and post-grant proceedings. Historically, the threshold for reliance upon post-filed data before the EPO has been a relatively modest one. This much is recognised in the Guidelines for Examination in the European Patent Office in the context of the problem-solution approach to the assessment of inventive step (G-VII, 11):

“The relevant arguments and evidence to be considered by the examiner for assessing inventive step may either be taken from the originally filed patent application or submitted by the applicant during the subsequent proceedings.” [Emphasis added.]

However, a carte blanche pertaining to the use of post-filed evidence does not exist for applicants before the EPO, with the guidelines further noting that (vide supra):

“Care must be taken, however, whenever new effects in support of inventive step are referred to. Such new effects can only be taken into account if they are implied by or at least related to a technical problem initially suggested in the originally filed application.” [Emphasis added.]

The notion that post-filed evidence may only be used to support the original disclosure of a patent application and may not be relied upon as the sole basis for inventiveness, is highlighted in a number of seminal Board of Appeal decisions from the early 2000s. T 1329/04 (John Hopkins), T609/02 (Salk Institute) and T578/06 (Ipsen) are frequently cited examples. The general theme arising from this line of “early” jurisprudence is conveniently summarised in the headnote to T 1329/04, as follows:

“The definition of an invention as being a contribution to the art… requires that it is at least made plausible by the disclosure in the application that its teaching solves indeed the problem it purports to solve… … even if supplementary post-published evidence may in the proper circumstances also be taken into consideration, it may not serve as the sole basis to establish that the application indeed solves the problem it purports to solve.” [Emphasis added.]

It would seem safe to assume that Board of Appeal 3.3.08 could not reasonably have foreseen the significance of its fateful utterance of the “P-word” in T 1329/04. In the years that followed this decision, the significance of “plausibility” as a concept in patent law snowballed well beyond the confines of the EPO to become a hotly debated topic in patent validity actions before national courts in the UK and Europe. The concept became firmly rooted in every savvy practitioner’s consciousness, to be ignored only at one’s peril, despite not actually appearing in the letter of the law.

Fast forward to T 116/18 and the concept of plausibility served three ways

On the face of it, the facts underlying the decision in case T 116/18 are fairly unremarkable. The patent which is the subject of the decision (EP2484209B) relates generally to a method of controlling an insect pest using a combination of known insecticides. As is fairly common in such cases, the patent proprietor sought to rely upon a synergistic effect associated with the claimed combination of active compounds, according to which the observed insecticidal activity for the claimed combination was purportedly greater than the sum of its parts, that is, more than a merely additive insecticidal effect was observed. During post-grant proceedings, the proprietor’s reliance upon post-filed evidence to demonstrate inventiveness was pivotal to the assessment of patent validity.

In reviewing the EPO’s jurisprudence relating to plausibility, the Board of Appeal in T 116/18 identified three divergent standards which it felt had previously been applied in assessing the threshold for reliance upon post-filed evidence. The legal thresholds identified by the Board of Appeal may be summarised as follows:

- Ab initio plausibility: post-filed evidence may be relied upon if the relevant technical effect(s) associated with the distinguishing technical features of the invention are plausible from the disclosure of the original application as filed.

- Ab initio implausibility: post-filed evidence may be relied upon if there is no reason to conclude that technical effect(s) associated with the distinguishing technical features of the invention are not plausible from the disclosure of the original application as filed.

- No plausibility standard: any and all evidence of a technical effect associated with the distinguishing technical features of the invention may be admitted. In effect, no threshold for the reliance upon post-filed evidence exists.

In light of the identified divergence, the referring Board of Appeal sought clarification from the Enlarged Board of Appeal as to allowability of post-filed evidence to demonstrate a technical effect and the legal threshold(s) to be applied in assessing whether such evidence may be considered.

The Enlarged Board of Appeal’s decision in G 2/21

Few observers were likely surprised by the Enlarged Board of Appeal’s response to the first referral question in T 116/18, although its answer may have prompted an inward sigh of relief in certain quarters of the profession. In short, the Enlarged Board of Appeal confirmed that the reliance upon post-filed evidence to demonstrate inventiveness is acceptable in principle, as summarised in headnote I of G 2/21 below.

“Evidence submitted by a patent applicant or proprietor to prove a purported technical effect relied upon for acknowledgement of inventive step of the claimed subject-matter may not be disregarded solely on the ground that such evidence, on which the effect rests, had not been public before the filing date of the patent in suit and was filed after that date.”

However, the Enlarged Board of Appeal’s answer to the second referral question was considerably less predictable, not least because of the seemingly conscious decision to omit any reference to “plausibility” in its answer, ab initio or otherwise. According to the headnote II of G 2/21.

“A patent applicant or proprietor may rely upon a technical effect for inventive step if the skilled person, having the common general knowledge in mind, and based on the application as originally filed, would derive said effect as being encompassed by the technical teaching and embodied by the same originally disclosed invention.”

Cue significant head scratching and blog posts. Come back plausibility, all is forgiven. But as the Enlarged Board of Appeal kindly reminded us, plausibility is but a catchword favoured by the Boards of Appeal and national courts, and nothing more. It is not, lest we forget, a distinctive legal concept of specific requirement of the European Patent Convention.

And so there we have it. A seemingly new legal standard to be applied in assessing the allowability of post-filed evidence in support of inventive step at the EPO. Fait accompli.

Life after G 2/21

Unsurprisingly, there was considerable anticipation concerning the direction that would be taken by the EPO when interpreting G 2/21, and eagle-eyed observers did not have to wait very long for the decisions to start rolling in.

The most complete guidance on G 2/21 to date has come from the referring Board of Appeal (3.3.02) in its final decision relating to T 116/18. In the referring Board of Appeal’s view, G 2/21 made it clear that patent applicants or proprietors do not have complete freedom to rely upon any purported technical effect at any stage of proceedings before the EPO. Fundamentally, the Enlarged Board of Appeal required there to be a threshold to prevent the filing of applications directed to speculative “armchair” inventions made only after the filing date.

The Board of Appeal noted that threshold set out in G 2/21 was two-fold and cumulative. For a patent applicant or proprietor to be able to rely upon a purported technical effect for inventive step, the skilled person would derive said effect as being:

- encompassed by the technical teaching; and

- embodied by the same originally disclosed invention.

In the Board of Appeal’s view, the assessment as regards requirements (1) and (2) has to be made based upon the broadest technical teaching of the application as filed with regard to the claimed subject matter. As such, requirement (1) may be met in the circumstances where the claimed subject matter is only conceptually comprised by the broadest technical teaching of the application as filed; meaning that the effect need not be literally disclosed, provided that the skilled person would recognise that the effect is necessarily relevant to the claimed subject matter. Such an approach would appear to provide applicants and proprietors with a reasonable degree of leniency.

With regard to requirement (2), the Board of Appeal formulated the following question as being relevant to the assessment of whether a particular technical effect is “embodied by the originally disclosed invention”:

“Would the skilled person, having common general knowledge on the filing date in mind, and based on the application as filed, have legitimate reason to doubt that the purported technical effect can be achieved with the claimed subject-matter?”

According to the Board of Appeal, requirement (2) is to be met unless the above question is answered in the affirmative.

At face value, the threshold applied by the Board of Appeal in reaching its conclusion appears not too dissimilar to the previously identified standard of ab initio implausibility. The Board of Appeal further confirmed that, in its view, it was not a necessary requirement for the application as filed to contain experimental proof that the purported technical effect is actually achieved for the subject matter in question; nor is it necessary for the application as filed to contain a positive verbal statement about the purported technical effect.

In other decisions, pleasingly we see consistency of approach, at least by Board of Appeal 3.3.02. In T 1825/21, although the Board of Appeal ultimately did not find it necessary to consider the post-filed evidence, it noted that the technical effects relied upon by the patent proprietor (stability and ease of drying) were “credible” on the basis of the information in the patent and the common general knowledge of the skilled person.

But what of sufficiency?

In G 2/21 the Enlarged Board of Appeal recognised the significance of prior EPO jurisprudence relating to the notion of plausibility and the requirement for sufficiency of disclosure under article 83 of the European Patent Convention (EPC), particularly in the context of medical use claims where a therapeutic effect is a technical feature of the claim. The Enlarged Board of Appeal endorsed what it considered to be the consistent and correct approach taken previously by the Boards of Appeal with reference to inter alia T 609/02, T 1599/06, T 754/11, T 760/12 and T895/13.

Although the questions referred to the Enlarged Board of Appeal did not require it to comment upon the interplay between plausibility and sufficiency of disclosure, the following helpful comments are given in paragraph 77 of G 2/21 in the form of an “Intermediate conclusion”:

“The reasoned decisions of the boards of appeal in the decisions referred to above make it clear that the scope of reliance on post published evidence is much narrower under sufficiency of disclosure (article 83 EPC) compared to the situation under inventive step (article 56 EPC). In order to meet the requirement that the disclosure of the invention be sufficiently clear and complete for it to be carried out by the person skilled in the art, the proof of a claimed therapeutic effect has to be provided in the application as filed, in particular if, in the absence of experimental data in the application as filed, it would not be credible to the skilled person that the therapeutic effect is achieved. A lack in this respect cannot be remedied by post-published data.” [Emphasis added.]

Credible = Plausible? Probably, per T 1394/21 citing G 2/21.

Other Boards of Appeal have also taken a position which might be seen as “pro-patentee”. The underlying patent in T 873/21 was directed to a combination of known compounds for a specified veterinarian use. Similar to T 116/18, the patent proprietor sought to rely upon post-filed evidence to demonstrate a synergistic interaction between the claimed compounds in relation to improved insulin sensitivity. In this case, the application as filed did not contain an explicit reference to synergy but that did not prevent the Board of Appeal (3.3.07) from finding that the synergistic effect relied upon was encompassed by the teaching of the original application. In doing so, the Board of Appeal noted that the application as filed made reference to improved insulin sensitivity in connection with the claimed combination and, in its view, the post-filed evidence amounted only to a quantification of the obtained improvement in insulin sensitivity described in the original application.

In T 1891/21, the Board of Appeal (3.3.05) found that the examples of the contested patent supported the technical effect upon which the patent proprietor had relied upon to demonstrate non-obviousness and that there was no counter-evidence to render the disclosure of the original application incredible. In such circumstances, the Board of Appeal had “no doubt” that the requirement of G 2/21 (headnote II) was met meaning that the proprietor may rely upon the same technical effect for the assessment of inventive step.

However, there are also a number of published decisions which suggest that life post G 2/21 will not be entirely plain sailing.

In T 258/21, the Board of Appeal (3.3.07) did not allow reliance upon post-filed evidence relating to a technical effect which, in its view, was neither contemplated nor even suggested in the application as filed. In this case, the patent claims were directed to clevidipine for use in a method of reducing ischemic stroke damage. The original application contained no experimental data relating to the claimed therapeutic indication but did contain certain statements regarding the compound’s biological activity: “The present invention is based on the discovery that clevidipine… is effective in reducing stroke damage and/or lowering blood pressure in a patient with a stroke… Clevidipine provides the optimal balance of efficacy, precision (titratability), and safety.”

In T 1045/21, the Board of Appeal (3.3.07) did not consider post-filed evidence to demonstrate a purported technical effect relating to improved drug efficacy in a particular patient group. The Board of Appeal noted that, according to established jurisprudence, if comparative tests are chosen to demonstrate an inventive step on the basis of an improved effect over a claimed area, the nature of the comparison with the closest state of the art must be such that the alleged advantage or effect is convincingly shown to have its origin in the distinguishing feature of the invention compared with the closest state of art. With reference to G 2/21, the Board of Appeal also noted that, “It rests with the proprietor to properly demonstrate that the purported advantages of the claimed invention have successful been achieved.” In this case, that requirement was deemed not to have been met.

Has the EPO hit the reset button?

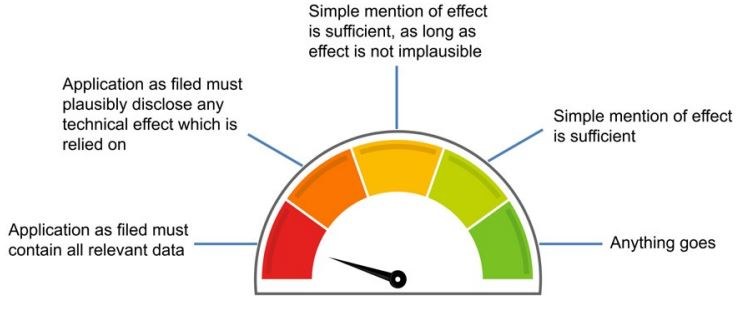

As patent attorneys, of course, we like some drawings to accompany our description, so how does G 2/21 fair in a pictorial scale? Our proposed scale (figure 1, below) ranges from an “anything goes” level at the bright green end, where patentees and applicants might be able to file any new data they like, to a “no additional data under any circumstances” level at the red end, via something akin to ab initio implausibility (yellow) and ab initio plausibility (orange) in the middle.

We can probably all agree that the two ends of the spectrum, red and bright green, are not, and never have been, appropriate measures of the requirements for introducing post-filed data. So, ignoring these, at the most generous end of the scale a simple verbal mention of the relevant effect in the specification as filed might be considered a minimum requirement. This is perhaps a reflection of the provisions on reformulation of the technical problem (Guidelines for Examination in the European Patent Office, G-VII, 11 as referenced above). Pre-G2/21 practice, though, was generally understood to require more than this. Decisions such as T 1329/04 (John Hopkins) and T 488/16 (Dasatinib), moved us at least into the yellow, if not the orange zones. And there was a sense that the practice of the EPO had been (at least before some Boards of Appeal) moving more firmly into the orange area in recent years.

So where on this scale does G 2/21 leave us? It does seem that the Enlarged Board of Appeal has used G 2/21 to give us a bit of a reset. But if so, how far back on the dial have we moved?

One possible interpretation, given the additional guidance we have from the referring Board of Appeal in T 116/18 is that G 2/21 pushes us back at least to the yellow zone. One might interpret G 2/21’s requirement (1) as akin to the green zone, a simple mention of an effect is enough. But this does not seem to square with the clear direction from the Board of Appeal that requirement (2), which is more akin to the yellow zone, is an additive requirement. It seems that an invention which simply is not credible without some kind of evidence, does still need to meet the same low threshold test as discussed in T 1329/04. Armchair inventing is still not on the cards. But an invention that is credible on its face can happily sit in the green zone, and further evidence can be relied on as long as the technical effect is within the teaching of the application as filed.

One way or another, it seems reasonable to conclude for the time being at least, that the prevailing winds of the EPO are aligned in favour of applicants and proprietors seeking to rely upon post-filed evidence to support inventiveness. Cue the introduction of creative arguments raised by opponents that a skilled person would have had, as the Board of Appeal in T 116/18 put it, “legitimate reason to doubt that the purported technical effect can be achieved”. One point we can be sure of is that there will be lots more decisions to come.

Conclusion

Although following G 2/21 and subsequent related decisions we have a degree of welcome clarity concerning the role of post-filed evidence in the assessment of inventive and sufficiency, the jurisprudential dust has not entirely settled.

A petition for judicial review of T 116/18 was filed in January 2024 by the opponent/appellant according to which it has been requested that the Board of Appeal’s decision be set aside and that the proceedings be re-opened on the basis of a fundamental violation of the petitioner’s right to be heard. Petitions for review are an extraordinary legal remedy and it is generally challenging to convince the Enlarged Board of Appeal of their admissibility. Therefore, only time will tell whether this particular petition (designated as R 04/24) will be successful or not.

In the meantime, the Enlarged Board of Appeal’s two-step threshold remains…and please don’t mention the P-word.

Useful link

This article was first published in the CIPA Journal (March 2024 / Volume 53 / Number 3) of the CIPA Journal entitled “Life after G 2/21: Plus ça change, plus c’est la méme chose?”. CIPA members can access the journal via the CIPA website:

Read more (subscription required)